“Can we check the mailbox to see if we got a letter again?” has become a common first question of the day in my preschool class. The “mailbox” is an old shoebox that my students decorated with drawings glued haphazardly across the cardboard, featuring a picture of a snail with an envelope and a little red flag that I affixed to the side. Inside, my students are greeted by a simple piece of paper nearly every day, which has become the cornerstone of my teaching practices in this last month.

Throughout the year I had felt like a ringleader in a complicated circus act. My read-alouds always included big, engaging voices and silly faces. I sang songs and danced all of the dances, I brought children in close with a dramatic whisper and the promise of wonder. The energy felt akin to a hawker shouting Looky here! Over here! Follow the bouncing ball! Watch me pull constant classroom engagement out of my hat! Reader, this was exhausting and would leave me completely overstimulated by the end of each day.

I, like so many teachers in the last month of school had been hanging on by a thread. The big end-of-the-year feelings hit four-year-olds hard and it was getting difficult to make each day feel magical and fun in an authentic way. Routines felt stale, lines of inquiry and meticulously planned provocations fell flat. But then I found a copy of Frog and Toad in my classroom library, and everything changed.

There is something magic in simple storytelling; as a fervent, lifelong fan of Frog and Toad, it felt like an easy choice to simply sit down and read something that always brought me calm and comfort after a year of chaos and emotional upset. I opened the book and began to read and noticed that for the first time all year, the classroom was completely silent. The timing was perfect; it was April and we began to read the story Spring, where Frog convinces Toad to get out of bed by secretly changing his calendar from April to May, The Story left my students rolling on the floor laughing as they watched Toad try all manner of ridiculous things to come up with a story for his sick friend. The language was simple, the plots were short, and even with more than fifty years of distance between these stories’ initial publication and my reading them to a group of four and five year-olds, they still felt deeply truthful and earnest.

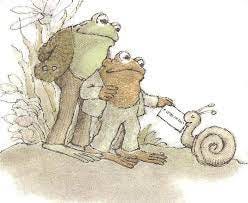

The real magic began when we read The Letter: In this story, Toad is sad because no one has written him a letter, and he sits by his mailbox desperately waiting for mail, but nothing ever comes. Frog writes him a letter and gives it to a snail to be delivered, but the snail takes days to get to Toad’s house with the letter from his friend. When Toad finally receives the letter he is thrilled and declares that this kind gesture was worth the wait.

Upon closing the book at the end of this particular story time, one of my students raised their hands and asked Teacher Carson, what’s a letter? It felt surreal to have to explain what a letter was to a group of children, but I spent a few minutes explaining that sometimes people send cards or notes to one another in the mail to let them know that they were loved or being thought of. This revelation was huge for my class and they all started to articulate the idea that maybe they could write letters to Toad; because if one letter made him so happy, several would make him even happier.

We started to dive into how to properly format a letter, its usual beginning, middle and end, and we wrote a collective class note to Toad telling him about how much we loved his stories. But then we encountered yet another problem: how would we send this to Toad? Again, the delight of four-year-old logic came into full swing and the children decided that we simply must have a mailbox. So they quickly went to work building a ramshackle mailbox out of what we had in our recycling.

The next day, they all came rushing to the mailbox that was stationed by the entrance of our classroom and noticed that the flag was down and their letter had been replaced by a reply from Toad himself.

Throughout the day the children asked me to read and re-read the letter and continually reveled in how kind it was that we got a reply. It was like a spell had been cast over the classroom and everyone immediately went to work making their own cards and letters addressed to Toad. Often I would write “DEAR TOAD” on the tops of their papers or on the white board for them to copy and they would either draw a picture or make their own attempts at writing that I would then caption for them.

Soon the mailbox became stuffed with papers of all shapes and sizes. Toad would receive their best artwork, their deepest thoughts, their wonders and their worries, they would tell him about their plans for the weekend and the dreams they were having, and every morning they would eagerly look for his reply in the little cardboard mailbox by the door.

Toad became more entwined with their day-to-day activities. After reading The Kite, the children insisted on flying a kite of their own in the field. The next day Toad would tell them that he and Frog were cheering for them as they watched the kite fly up high into the sky, and they would wonder at where their amphibian friends could have been. The children would wonder if they were normal animals or if they were magic since they wore clothes and spoke words. They would wonder how they could read our letters if we were so big and they were so small. They began to take more notice of the world around them and would revel in the small things that could be a clue as to where they could find their dear pen-pals.

In moments like these, it can become easy to get swept away in the magic of it all. But there is a certain weight that comes with it as well. When working with small children, you become familiar with the sense that everything you do has a possible permanent impact on the rest of their lives. Magic moments like this can become a lifelong source of wonder or a major disappointment they may return to in therapy years later. Every detail was important; I would come in early to print a new reply each day, I found a hiding space for the immense number of letters my students would send (this was a data goldmine for early childhood standards!) and I would listen closely to the conversations my students were having to ensure that Toad would address their questions or worries throughout the week.

Soon, we had a three-ring binder stuffed to the brim with all of their replies. Frog and Toad would begin asking for their help to identify snakes and insects, advice on how to build a boat, the class would be given scavenger hunts for missing buttons, collecting party supplies, making lists and telling their little friends scary stories on rainy days.

This had become bigger than me and yet it was me. Every message of love, every encouraging word, every question that I presented to these children was sincere. Parents started to approach me asking what this project was because it was all their child would talk about coming home each day. “This is more important to him than Santa and the Tooth Fairy” one parent told me. Families started investing time and energy into extending the magic into their homes too. They found the Frog and Toad animated series, they would re-read the stories to their children, they would go on walks and look for clues as to where the characters could be. What had initially been a one-off event had wrapped an entire classroom community in magic and wonder. Something that has been in short supply these past few years.

The magic of stories is something I have championed for years, but I have never been given such a deep and engaged set of minds to explore this magic with until now. In a world of climate change and genocide and political unrest, it seems the opportunities for genuine childhood joy are dwindling. As the COVID-19 pandemic began, I watched children stop playing pretend and start playing dead. I regularly encounter children who are climate refugees, having moved across the country after their homes have been destroyed by wildfires or floods. With all this in mind, it feels as though creating a sense of magic is more important now than ever.

In the last full week of school, we climb the steep hill to the pond and marvel at its depth from the immense bouts of spring rain. The cicadas buzz overhead and the deep thrum of the American Bullfrog rings through the air. We walk around the edge of the pond and everyone stops, eyes wide. Still as can be, a perfect green frog stands on the shore and the children all gasp, it’s him, it’s him! It’s Frog, I can’t believe it! I watch as they all sit down slowly and quietly as a voice just barely above a whisper calls out

Hello Frog, it’s us, your friends. I’m so happy to finally meet you!

Because I love you:

Add this to your playlist: Chappell Roan - Good Luck, Babe!

Add this to your reading list: Heavier than Wait - Ilyus Evander

Add this to your Watchlist: Dropout TV - Game Changer

'til next time friends

Ugh I was not prepared to cry this morning Carson 🥹 you are truly creating beautiful lifelong memories for those kiddos and that matters so much. It’s reminding me of teachers I had when I was little who made similar kinds of magic - I’ll never forget the wonder and I’ll always feel so much gratitude for their thoughtfulness and care. 💚

This is so beautiful! We are going to begin pre-k homeschool with our four year old this summer and frog and toad is our first choice. So much magic in friendship.